This week is the 70th anniversary of the NHS. It was an extraordinary promise by a society to care for all its members, free at the point of use. It went rapidly from plan to reality in just three years and, decades later, as a mark of its success, the NHS still comes top of international health service league tables. But the triumph of its public ethos is not found in targets and tables, but the people who’ve made it, and had their own lives shaped by the NHS. Here is the story of just one person like that, my mother, June Simms, who went from being a young patient in the first days of the NHS to one of its first nurses and a midwife. And, of course, for anyone who has lived in the UK since its birth, the NHS is part of the story of all of us.

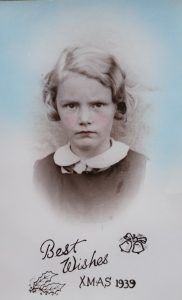

June Simms, aged 7

In the summer of 1948, as a 16 year old girl, June Simms became one of the first people to benefit from the newly created NHS. It changed the course of her life. She grew up in a working class home in the Midlands where there were few luxuries. But, like many children, she loved dancing and from the age of 7, cheap dance classes became a distraction from the war that raged in the skies above her head.

Her father, Fred, was an Air Raid Warden, and one of his jobs was to go into Coventry after devastating bombing raids. From the opening of the damp and frog infested Anderson bomb shelter in her garden in Rugby, she saw the night sky glow red as the city burned. Dance allowed escape, and proudly she would perform for her parents. But, an inexperienced young teacher made her pupils, including June, go on ‘en-pointe’ – dancing on their toes – far too young, and before their bones were properly formed.

Hear June towards the end of this 2011 BBC News radio story on the ‘New Home Front’ talking about environmental lessons to be learned from war time experiences

By 16, both of June’s feet were permanently damaged. Walking was painful and she needed surgery. Without the arrival of the NHS that year – part of the new social promise to emerge from the war-time experience of collective endeavour – her family could never have afforded the necessary operation. The kindness and care that she received from the first NHS nurses left a huge impression and planted the idea that she, too, might train to become an NHS nurse.

With that in mind she left her school 6th Form after one year and began preliminary nurses training, a six week course in January 1950, which included working on wards on Saturdays. From there she began her three-year training as a State Registered Nurse (SRN) at the Hospital of St Cross, Rugby. In that time she picked up several prizes for her achievements, before going on to work as a Staff Nurse at the hospital for six months. Moving to London in 1954, a city still gripped by post-war austerity, she trained for her First Part Midwifery at the Lambeth Hospital, in a poor neighbourhood near Elephant and Castle. June remembers how common were conditions like rickets in children, problems associated with poverty.

She completed her midwifery training in Welwyn Garden City. In photographs of her, with the life-long friend, Hilda, she’d made during training, they look as if they have walked off the set of Call the Midwife.

Call the Midwife

Then she saw an advert in the Nursing Times for a course in plastic surgery, still innovative at the time, at the Churchill Hospital in Oxford. It grabbed her imagination and she began the equivalent of six months post graduate training. “It was really interesting” says June, “working on both the children’s and adults’ wards.”

Then she studied still more for the demanding role of being a Theatre Nurse. “I liked this best of all,” says June, “I felt I was in the right place doing the right thing. In those days when you started, you packed drums with surgical instruments, boiling them up for sterilising. You acted as a ‘runner’ and had to lay up trollies. Then you worked your way up to be Assistant Nurse at operations – ‘scrub-up nurse’ – gradually working towards taking part in complicated operations.”

When you became a staff nurse you were entitled to wear a silver buckle on the belt of your uniform. June bought hers from the first Oxfam shop in Oxford. After being at the Churchill for another six months, she was offered the job of Junior Theatre Sister – one of only three across various operating theatres.

But the early NHS wasn’t all work and no play. Having lived through hard times she thought “Oxford was lovely, not crowded, I enjoyed being there. Full stop. We went to the Playhouse and events at Blenheim. We went Youth Hostelling. One Easter we took a trip to Bournemouth and it snowed. And I remember Christmas dinner and dances at the Randolph.”

Applying her NHS training at home

One day, pinned to the nurse’s noticeboard at the Churchill, June saw an invitation to a dance at the Oxford City Hockey Club. The young man who came to collect her from the nurse’s accommodation, in his father’s ancient automobile, was David Simms, from an old Oxford family of stonemasons, carpenters, builders and firemen, a family with a history in the town going back hundreds of years. He was the man June would leave the Churchill to marry in 1958. But that wasn’t the end of her commitment to using her NHS training. She later worked on a gynaecological ward at St Helier’s Hospital in Surrey, and after raising three children (in which her training came in very useful, at least where one accident prone son was concerned), she worked for several years as the staff nurse at Essex County Council’s headquarters in Chelmsford.

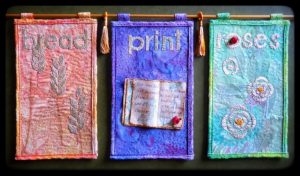

In many ways June’s training – in terms of its attention to care, meticulous preparation and organisation, and even stitching skills, prepared her for her second career. In 1977 she read an article in a colour supplement about the textile artist Beryl Dean and was inspired. She went back to study part time for 4 years and developed her skills and creativity in embroidery-based textile art. She has taught, and exhibited continuously ever since. A sample of her work can be seen in a commission for Bread, Print & Roses in which she takes the style of a union marching banner and produces a work in honour of women who have had to fight for their rights.

This work, and the phrase ‘bread and roses’ is inspired by striking women textile workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts in 1912.

Her latest piece – Threads in Time (2018) – an autobiographical work produced to mark the NHS’s 70th anniversary and exhibited at the Oxford University Hospitals special exhibition at the Churchill – is informed by the colours of the uniforms she wore in those early days of the service back in the 1950s.

June Simms exhibits in the gallery in the Oxford hospital where, 60 years earlier, she used to work

I enjoy the wide range of textile surfaces that I can achieve with a variety of dyed and stitched fabrics, from crumbly stucco walls to shimmering water.

This is June Simms in her own words talking about her work today:

“My work explores the melding together of fabric, paint and thread using hand and machine embroidery. These elements are combined in wall hangings, textile jewellery, bags, boxes and mirrors. Inspiration comes from many sources: ancient mosaics and ruins, my son’s underwater photography, Essex gardens, ethnic jewellery and now my time working in the NHS as well!

I enjoy the wide range of textile surfaces that I can achieve with a variety of dyed and stitched fabrics, from crumbly stucco walls to shimmering water. I am a member of the Essex Embroiderer’s Guild and have exhibited at a wide range of venues.”